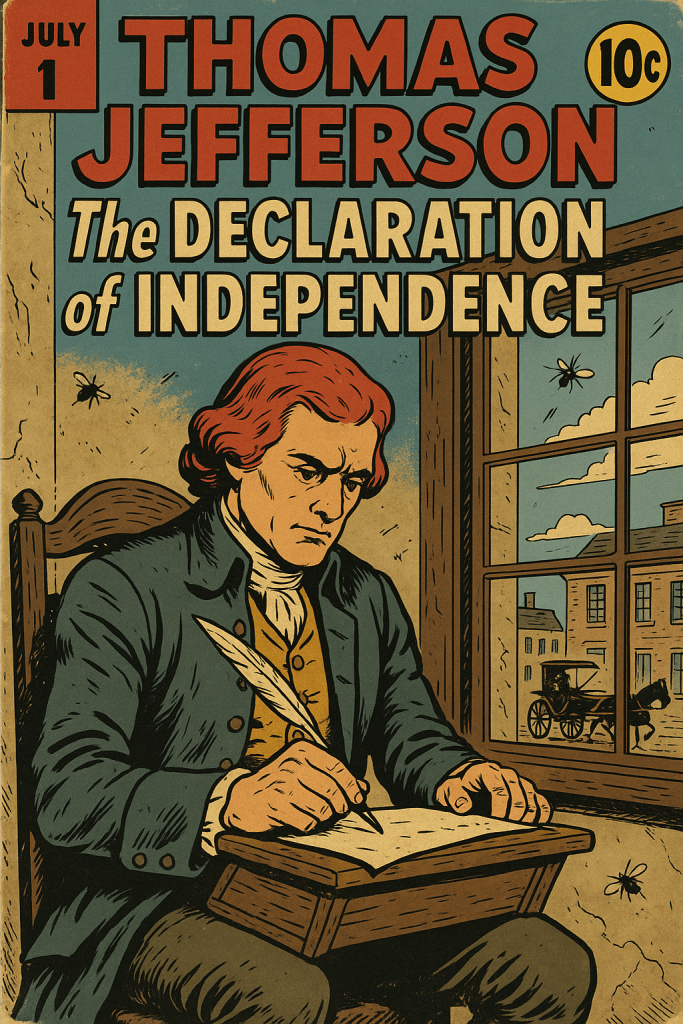

Persistent houseflies buzzed through the stillness of the second-story parlor, interrupted only by the occasional clatter of passing carriages on the street below. Inside, a young red-haired Virginian wrote with quiet intensity—his pen moving with both duty and passion.

Anxiety and excitement coursed through his thoughts as he crafted what the British Crown would surely consider an act of treason. Each word, each phrase, was chosen with careful deliberation, drawn from a well of literature, history, and religion. Yet even as he wrote, he couldn’t help but wonder what fate awaited his life, his family, and his farm.

Thomas Jefferson sat with a portable writing desk—his own design—balanced on his lap, working briskly through the increasingly warm Philadelphia days of June 1776. Though the words came from his hand, he never claimed they were entirely his own. Each sentence stood on the shoulders of ancient republics, enlightenment thinkers, and Judeo-Christian ideals. And within them, he etched a phrase that would echo across generations:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

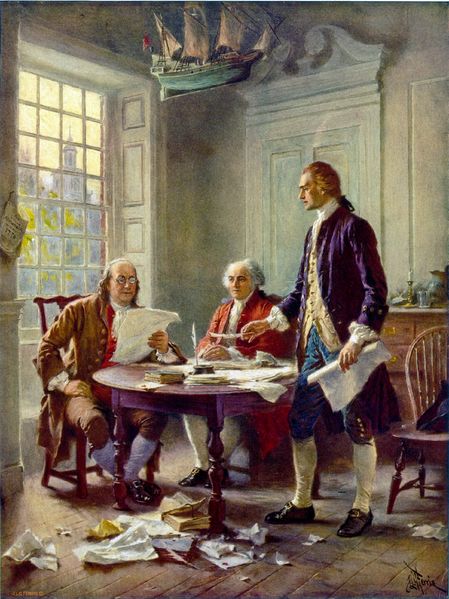

Jefferson had been chosen by the Committee of Five—John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston—to pen the draft. Adams later claimed he was offered the task but deferred, saying:

Reason first: you are a Virginian and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason second: I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular; you are very much otherwise. Reason third: You can write ten times better than I can.

Jefferson, however, recalled no such exchange, suggesting the decision was simply made by committee. Their conflicting accounts, offered in old age, may reflect fading memories more than clashing egos. In truth, had any of them written it, the core message would have remained largely the same—for they all read the same authors, believed the same principles, and felt the same call for liberty.

Philadelphia, PA

Nearly four years before Jefferson took up his pen, Samuel Adams had already captured the spirit of the revolution in The Rights of the Colonists, writing:

…the Natural Rights of the Colonists are these: First, a Right to life; Secondly, to liberty; thirdly, to property; together with the Right to support and defend them in the best manner they can.

Only one word differed: property, later refined to the more universal and aspirational pursuit of happiness.

But even Samuel Adams was echoing a voice from deeper history—John Locke. In his Two Treatises of Government, Locke wrote:

Being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions.

In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke further explored the concept:

The highest perfection of intellectual nature lies in a careful and constant pursuit of true and solid happiness… the necessary foundation of our liberty.

These rumblings of revolution began in the late 1600’s but would take roughly a hundred years before the first musket blasts were fired in defense of these principles.

What is the result of these famous words? These great men set up the secret formula, an equation never tried before in government. Instead of building an all-powerful government, ruled by kings or dictators, they embarked on a new experiment—self-government. A government where each person is free to live their life and tend their property as they see fit, so long as it does not infringe on the life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness of another.

Happy Independence Day! 🎆🇺🇸